Building a Leadership Culture

Tom Goodell

In a leadership culture the practices of innovation, visioning, execution, and reflection arise everywhere in the organization, and everyone’s behavior is characterized by high degrees of honesty, trust and accountability. The Four Fields of Leadership and the Cycle of Leadership provide a framework for intentionally building and maintaining a leadership culture.

Watching organizations wrestle with seemingly intractable leadership problems led us to a careful examination, and ultimately a profound redefinition, of leadership. In our work we repeatedly observed certain patterns in organizations where leadership went well and other patterns in organizations where it didn’t. In organizations where leadership went well, communication channels were open between leaders and followers. People felt it was safe, even welcome, to share their thoughts and opinions, both positive and negative, with their leaders. If a leader made a request that was not clear, people would ask for clarity before taking action. Such a request was welcome. If trust began to break down between any two people the skills were in place to address the problem quickly and trust was restored. The mood in such organizations was generally optimistic; the culture was permeated with the belief that collectively they could solve any problem.

In organizations where leadership didn’t go well, traditional approaches to leadership, which focused on fixing the leader, frequently failed to address the problem. In these organizations we observed that the communication lines between leaders and followers were often weak and characterized by mistrust. People were afraid to challenge their leaders, and the requests leaders made of their people often had the quality of demands. If the demands were not clear, the people receiving the demands did not feel it was safe to ask for clarity—and indeed, it usually wasn’t.

Rumor mills were rampant in these organizations, and people spent considerable time talking with one another about what was wrong with the leaders. Trust throughout the organization was low and resentment and cynicism were common. The leaders were either oblivious that any of this was going on or they chose to ignore or deny it. When we observed organizations that went from ineffective to effective leadership, or vice versa, we could observe the corresponding shift in culture.

Over time and across diverse organizations the patterns described above became clear, and we saw that a new definition of leadership was needed. We began to consider leadership differently, as an attribute of a culture rather than an individual, and asked questions that probed leadership effectiveness from that perspective.

Consider the following example which is based on real world experiences. In one company the CEO declares that the company will grow through acquisition of a competitor. The leader has not yet determined the specific competitor that will be acquired, but has some ideas. They want the acquisition completed in twelve months. The people in this company respond quickly, engaging the leader in conversations to clarify her or his intentions and concerns, helping to identify and evaluate candidates for acquisition, move through the negotiations, and close the deal within twelve months. In another company of similar size and makeup the CEO makes the same declaration. Again they have not identified the specific competitor to acquire, but they have some ideas, and they would like the acquisition to be completed in twelve months. In this company the response is quite different. People do not engage the leader directly, but they talk in the hallways and private meetings about all the problems with this idea. They do not take accountability for the declaration, they fail to take effective action, and a year later no acquisition has occurred.

In looking at these companies, one would be inclined to say that in the first company there was excellent leadership and in the second there was poor leadership. We would agree. What is interesting is where the difference lies—not in the words or actions of the leader, but in the dynamics of the organization’s response. It was repeated experiences like these, in which the breakdown was clearly not just in the person who held the role of leader but rather in the broader dynamics of the organization, that led us to rethink the meaning of leadership.

Defining leadership as an attribute of an organization’s culture broadens the scope of where one looks to improve leadership. Rather than focusing exclusively on the personal traits of individual leaders we also studied the ways relationships, behavior patterns, and communication practices throughout the organization impacted the quality of leadership and organizational performance. We found that organizations that exhibited effective leadership and sustainable high performance had cultures in which people’s behavior reflected a high degree of integrity and accountability, interpersonal relationships were maintained with high standards of honesty and trust, and communication flowed freely and effectively, ensuring that everyone had the information they needed at all times.

As we worked with our clients to establish leadership cultures we defined the Four Fields of Leadership:

- The Field of the Self

- The Interpersonal Field

- The Field of Teams

- The Enterprise Field

In all four fields, communication is the essential ingredient that determines performance. From this perspective, leadership development must include people and roles beyond identified leaders, and must develop a culture characterized by skills, relationships, and dynamics that are often beyond the scope of more traditional ways of thinking about leadership.

Seeing leadership as a characteristic of a culture reframes the role of the leader from one of “telling people what to do” or “inspiring people” to one of ensuring that the relationships, behaviors, and communication patterns within the organization meet the standards of a leadership culture. It is vital that leaders exemplify these standards in their own behavior. One of the many benefits that arise from this reframing is that the isolation leaders often feel dissipates as they experience themselves leading a team of committed followers.

ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE AND THE CYCLE OF LEADERSHIP

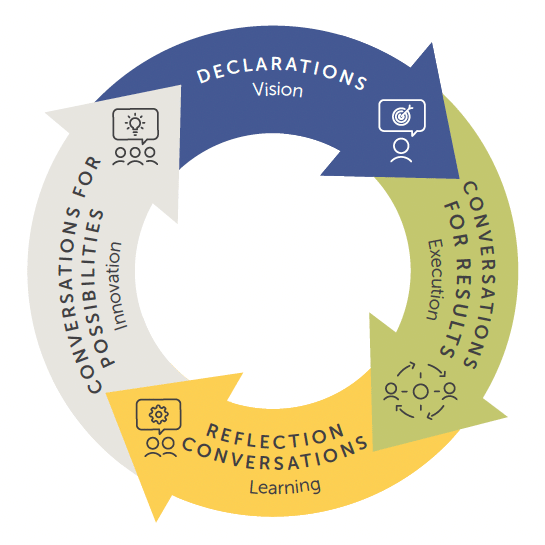

When leadership is recognized as an attribute of an organizational culture it is immediately apparent that communication is at the foundation of leadership. We have identified four Practices of Organizational Performance—a set of critical communication skills that are necessary for building a leadership culture. At a high level, these practices can be summarized as:

- Engaging effectively in Conversations for Possibilities

- Making effective Declarations

- Engaging effectively in Conversations for Results

- Engaging effectively in Reflection

Conversations for Possibilities: In Conversations for Possibilities leaders engage a variety of people to develop a deep sense of what is possible and how their people view the current and potential future states of the organization. To have effective Conversations for Possibilities, leaders must establish a culture in which people are free to speak their minds, engage in rich dialog, and transcend limiting beliefs to discover possibilities that might not normally occur to them. Conversations for Possibilities are where innovation happens. They are an essential capability for leaders and leadership cultures. It is here that leaders discover new possibilities and refine their own thinking and vision.

Effective leaders routinely engage a wide variety of people within and beyond their organization in Conversations for Possibilities. Beyond the richness of idea generation, Conversations for Possibilities provide an environment in which leaders can establish trust, respect, and buy-in from those they lead. When people feel their voices have been heard they are far more likely to be on board with the decisions made by leaders, even when they disagree with those decisions. They are also far less likely to feel blindsided and resentful when decisions are announced.

Declarations: From these conversations leaders make decisions and declare a future objective, or mission. Effective leaders cultivate the ability to make powerful declarations. Declarations are statements that define a future state. A powerful declaration does so in ways that engage and inspire people to get on board and stay on board to fulfill the declaration.

Powerful declarations are an essential element of the Cycle of Leadership. Because many people have been engaged in Conversations for Possibilities before the declaration is made, buy-in is high. And because people know their leader listens to them, and expects honesty, they will challenge when the declaration is not sufficiently clear or they perceive flaws or blind spots in it. Leaders invite and welcome these conversations.

Conversations for Results: Having engaged their people in Conversations for Possibilities and spoken a declaration, the leader must make clear requests to others to take responsibility and accountability for fulfilling particular roles in realizing the declaration. Requests and promises are the elements of Conversations for Results. Again, the leader must expect—and get—honest dialog with his or her people in these Conversations for Results before receiving promises to fulfill the requests.

Reflection: Reflection is the hallmark of learning organizations. In leadership cultures, leaders are fully committed to their own ongoing learning and to cultivating learning throughout their organization. Learning that is most relevant to leadership cultures is not technical learning. Rather it is the continuous development of communication and relationship skills. Leaders exemplify this in their own efforts to communicate well and build effective relationships, and in their expectations that others will do so as well.

Conversations for Possibilities are the engine of innovation; it is in these conversations that creative thought gives rise to possibilities that might otherwise never be discovered or considered. When declarations are made, visions for the future are established, around which the organization can rally and find common cause. Conversations for Results are the engine of execution; it is here that the actions necessary to fulfill the mission are defined, roles are clarified, and individuals commit to fill the roles and ensure the mission is fulfilled. Reflection is the engine of learning. It is a vital attribute of leadership cultures. In reflection, individuals and teams routinely stop and ask themselves these two questions: what did I/we well, and what could I/we do better.

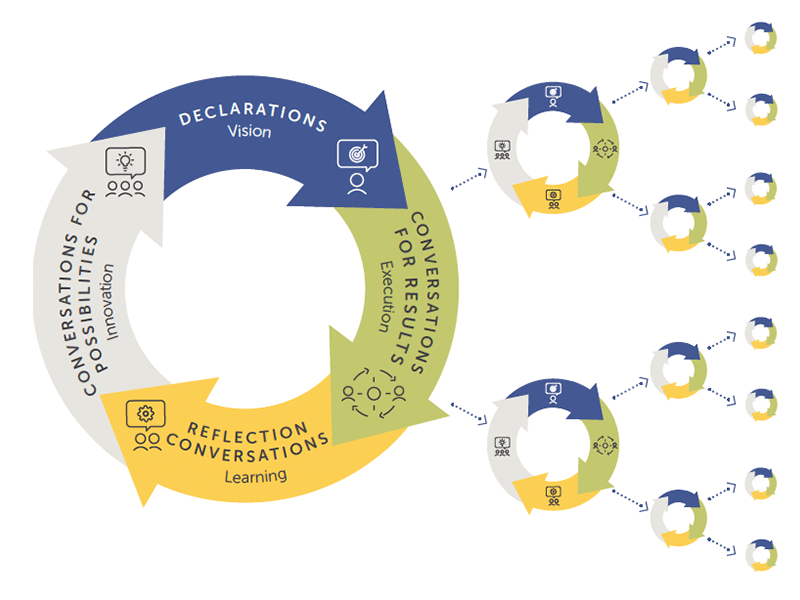

The Four Practices of Organizational Performance establish innovation, visioning, execution, and learning throughout the organization. Innovation, visioning, execution, and learning collectively form the Cycle of Leadership that is the hallmark of a leadership culture. In a leadership culture innovation, vision, execution, and learning arise everywhere, continuously. Because the Cycle of Leadership is a cycle it has no true beginning or end. However, it is often useful to think of it as being initiated by Conversations for Possibilities.

The Cycle of Leadership highlights a critical element of leadership cultures that is often overlooked in leadership development: the degree to which leaders can be effective is directly proportional to the degree to which those they lead—and others—will be completely honest with them. If a leader creates or inherits a culture in which others will not openly share their ideas in Conversations for Possibilities, will not challenge them for clarity and purpose in their declarations, will not negotiate for clear requests before making promises to perform, and will not commit to ongoing learning, the leader’s effectiveness will be diminished. Their declarations will be ill-informed, people will not be energized to get on board to fulfill the declarations, the execution of the organization will be mediocre, and there will be no opportunity to learn better ways. On the other hand, a leader who creates a culture in which fully honest conversations are the norm will have a highly engaged following that will be passionate about collectively realizing the declarations spoken by their leader and continuously improving their performance.

We consider anyone who engages in the activities of the Cycle of Leadership to be a leader, whether they hold a leadership position on the org chart or not. In this sense leadership is an emergent property of the culture and everyone contributes to leadership in a variety of ways.

THE FOUR FIELDS OF LEADERSHIP

The Cycle of Leadership establishes the dynamics that are necessary for a leadership culture. However, the Cycle of Leadership is much more than a mechanical process, and promoting the mechanics alone is not sufficient to create a leadership culture. For the dynamics of the Cycle of Leadership to take root in a corporate culture the disciplines of the Four Fields of Leadership must become norms for individual and collective behavior, and they must guide relationships throughout the organization.

DISCIPLINES IN THE FIELD OF THE SELF

The Disciplines in the Field of the Self are:

- Awareness

- Choice

- Accountability

Awareness: Awareness is the ability to notice, and accurately interpret, what is happening in your self and in others. For example, being aware that the team you lead is not aligned around a shared goal is essential if you are to get the team on track and keep them there. Likewise, being aware that your trust in another person has diminished is vital if you must interact with them to get your work done. If you are not aware that trust has diminished, the lack of trust will unconsciously influence your behavior in ways that are detrimental to your ability to work together, and since this influence is unconscious you will not be able to do anything about it. If you are aware that trust has diminished you can choose how it influences your behavior, and you can take steps to restore trust.

Kathleen, a leader we worked with in a distribution center, described her experience: “Through awareness practices I realized that I often came into team meetings assuming that things would have gone bad. That was my mindset. It colored everything I heard in the meeting. People were coming to the meetings with more and more anxiety; some people started having excuses for not showing up at all. I was getting increasingly frustrated, because I knew the team wasn’t performing well, but I had no idea how much I was creating that situation. When I started paying attention to how I felt prior to the meetings, and how that influenced my thinking, I realized there were things I could do differently. My behavior up to that point had caused mistrust to grow on the team.

“Once I understood what was happening, and my role in it, I was able to shift to behaviors that rebuilt trust. It wasn’t easy—I had to swallow some pride— but the result is that today the team is aligned, performs really well, and has a lot of trust in me and in each other.”

Awareness is the foundation on which the other disciplines of the four fields are built. The degree to which you are aware of yourself and others has a deep influence on your ability to make effective choices, take accountability for your actions, and build a high degree of trust in your relationships with others. This is a lifelong effort; we always have more to learn about ourselves.

Choice: Choice is rooted in awareness. You can only make choices about things you are aware of. If you are not aware of your own moods and beliefs—e.g., that you are angry or believe that someone has a hidden agenda—then your anger or belief will dictate your behavior and you will have no choice in the matter. Likewise if you are not aware of another person’s moods and beliefs you cannot make wise choices about how to interact with that person. In the example above, Kathleen, the leader in the distribution center, became aware of the mood on her team before noticing anything about herself. Without practice we most commonly notice things outside ourselves before we notice our inner state. When we began our work with her she was very frustrated with her team and wanted us to “fix them.”

Through coaching and awareness practices she realized that her behavior—and, even more fundamentally, her beliefs and emotional state—had a significant influence on the team. With this awareness she was able to make different choices. She started preparing for team meetings by paying attention to her tendency to assume that things would have gone badly. She realized that this assumption induced in her an emotional state of mistrust, resentment and blame, and that it was no coincidence that the mood of the team had also become one of mistrust, resentment and blame.

It is important to mention that the coaching and awareness practices, and subsequent shift in choices, did not lie exclusively with Kathleen. We also worked with her team— they too needed to increase their awareness capabilities, and they also had to acknowledge and shift the choices they were making about how they related to one another, to their work, and to Kathleen.

Accountability: Accountability is a personal choice to make a difference in some area of your life, your work, or the world at large. We draw an important distinction between accountability and responsibility. Responsibility, in our terminology, is a commitment to fulfill a defined role and to ensure that the tasks associated with that role are completed. Accountability is more personal and involves a deeper level of commitment than responsibility. Accountability is inherently an emotional choice—it involves caring about something and being committed to having a positive impact on it.

In the example above the members of Kathleen’s team were not responsible for leading the team, but any one of them could have taken accountability for it and approached Kathleen to talk about the impact her behavior had on the team. In fact, none of them did so. Instead they talked amongst themselves behind her back, which exacerbated the dysfunction of the team. This is common—if you are not operating in a leadership culture, approaching your leader with feedback they might not welcome is often a risky endeavor.

Kathleen could have chosen to continue blaming the team, taking the attitude that their dysfunction wasn’t her fault, and that her job was to demand that they clean up their act. Instead, upon careful self-reflection, she made the emotional move to acknowledge her own behavior and its impact, and to take accountability for addressing the problem. That move alone changed how the team perceived her and went a long way towards shifting their dynamic. As her behavior changed, and they came to trust that she sincerely wanted to show up in a way that served them, they were able to acknowledge their own beliefs and behaviors and take accountability for the performance of the team. What had been a situation of unacknowledged conflict between a leader and her team became a situation of collective accountability and collaboration.

As a leader you have the right and the authority to expect your people to choose accountability. In the Cycle of Leadership the role of a leader is to establish a culture within which the dynamics of the Cycle of Leadership are alive and well everywhere. This requires a culture in which accountable behaviors are acknowledged and rewarded, and people are chosen for roles not just on their technical abilities but also on their commitment to be accountable for the performance of the organization beyond their own immediate areas of responsibility. That requires a culture of accountability—one of the hallmarks of a leadership culture. A leader’s job is to create that culture.

DISCIPLINES IN THE INTERPERSONAL FIELD

The disciplines in the Field of the Self are the foundation of all human performance; to the extent that individuals are aware, make the best choices available to them, and take accountability for their actions, they will lead effective lives and be productive contributors at work. But life and work extend far beyond the individual—how your life and work unfold is as dependent on your relationships with others as it is on your own behavior. The disciplines in the Field of the Self are the necessary foundation for building and maintaining effective relationships with others, but they are not sufficient. In the Interpersonal Field another set of disciplines comes into play.

The disciplines in the Interpersonal Field are:

- Honesty

- Integrity

- Trust

Honesty: Honesty is a critical element of leadership cultures. We see honesty as being more than “telling the truth” because “truth” has many layers. The degree of your honesty is proportional to the degree to which you reveal yourself. Telling someone your surface opinion, but not revealing your deeper beliefs or emotions, is a shallow level of honesty. Real honesty requires courage and commitment, and a willingness to be vulnerable and to trust others to respect what is true for you.

Thus, honesty is clearly linked to awareness—you can only reveal to others those things you are aware of in yourself. In the distribution center example above, Kathleen was initially unaware of her underlying beliefs and emotional state, and her level of honesty was therefore limited to telling her team how unhappy she was with the results they were producing. As her self-awareness increased she was able to acknowledge—and take accountability for—her past behavior. The moment she told her team that she realized she’d been unfairly critical and had not acknowledged some of their good work was a powerful turning point in the evolution of the team. What had been a double spiral of diminishing trust and rising resentment began to reverse itself. People gradually learned that it was safe to be honest and to take accountability for the ways they had contributed to the under-performance of the team. The awareness levels of everyone on the team, the choices they made to be accountable, and their level of honesty, were all on the rise.

Integrity: Integrity is a measure of how fully your inner truth lines up with your words and actions. If you operate from a state of high integrity then what you care about and how you intend to influence the world around you are in complete alignment with what you say and do. Your actions and intentions are fully transparent to others in your life.

To the extent that you are holding something back or saying one thing but intending something else, you are out of integrity. Integrity is deeply rooted in awareness, since you can only ensure that your actions align with your inner state to the extent that you are aware of that state. If you do not know you are mistrusting or angry, then those emotions will influence your behavior even when you are trying to send a different signal. People will often read the mixed signals as a lack of integrity.

Integrity is also deeply connected to honesty. In our definition, honesty is proportional to how much of yourself you reveal. If you do not fully reveal your beliefs and intentions you lack some degree of integrity in the conversation.

For the first year in which Kathleen led the team in the distribution center she was, to some degree, lacking integrity. In conversations after things had shifted for the better she acknowledged that she had always, on some level, been aware that there was something out of sync between how she was feeling and how she was behaving.

But she didn’t have the skills—the awareness—to bring the discrepancy into focus, study it, and resolve it. To her great credit she had the courage to develop those skills and to engage in the sometimes challenging self-examination that was necessary to resolve the inner discord, and finally to honestly acknowledge her prior behavior.

Trust: Trust is based on beliefs people have about one another. One of the key beliefs that must be present in order to have trust is that the person you are interacting with is operating from a state of integrity—that what they say is aligned with what they believe and what they feel.

In our example of the distribution center, Kathleen’s early behavior with the team, and their behavior with her, gave rise to mistrust on both sides. Her team could see her frustration, but felt that she was not taking accountability for her behavior, that she was not being fully honest with them, and that she was therefore not operating from a state of integrity. Over time they came to question her leadership capability. As a result of these beliefs their trust in her diminished. Likewise she became aware of their hallway conversations and could sense the judgments they were forming about her but not speaking to her. She began to believe that they were lacking in integrity, she questioned their capability, and she perceived them as unreliable. Trust was restored over time and through consistent work by raising the levels of honesty and integrity on everyone’s part.

THE DISCIPLINES IN THE FIELD OF TEAMS

Disciplines in the Self and Interpersonal Fields operate at the level of individuals and the relationships between them. These are the necessary foundation for building great teams, but by themselves they are not sufficient. Team dynamics are more complex, with greater risks and greater potential, than the dynamics among individuals. Just as the disciplines in the Field of the Self lead to the disciplines in the Interpersonal Field, an additional set of disciplines come into play in the Field of Teams.

The Disciplines in the Field of Teams are:

- Alignment

- Engagement

- Reflection and Learning

Alignment: Alignment is the discipline of getting everyone on the team going in the same direction. It involves defining a clear purpose, or mission, for the team, and making sure that everyone on the team has the same understanding and appreciation of that purpose. The purpose becomes their touchstone—a place to come back to whenever confusion or conflict about direction arises.

Without alignment different members of a team will pull in different directions, resulting in wasted time and effort, and unfruitful conflict. Members of the team will likely spend as much, or more, time and energy resolving the different directions each of them is going as they spend actually moving forward.

Engagement: In Engagement, a group of aligned individuals transforms into a group of attuned team members. Attuned team members are aware of what each is doing, constantly ensure their actions are in sync with each other, and support each other in the best possible ways. They have each other’s backs, and they all know it.

Engagement involves passion; it is where teams truly come to know that they are all in it together. And it is where each member not only agrees on the purpose, but becomes personally committed to fulfilling it.

Reflection and Learning: Reflection and learning are about moving forward rather than standing still or moving backward. High performance teams commit to learning rather than blaming. When things go awry they step back and honestly examine what happened and why, so that they may learn and improve, and not make the same mistake twice. They are constantly moving forward, reflecting on the past only to the extent that it serves the discipline of learning. Learning at this level requires deep honesty with one’s self and with others.

The disciplines of the four fields do not happen magically, and they are not something “you either have or you don’t have.” They can be intentionally cultivated and maintained; it is essential to do so if you intend to create a leadership culture.

If attention is not paid to these disciplines, the degree to which they occur will be left to chance. Some of the time, in some organizations, they will arise for a while. But the frequency of their appearance, and the degree to which they occur, will be considerably less than what is possible.

LEADERSHIP CULTURES

In a leadership culture the disciplines of the Four Fields, along with the dynamics of the Cycle of Leadership, guide the choices and behaviors of people throughout the organization. Establishing such a culture requires commitment from leaders, teams, and individual contributors. Leaders in particular must be committed to cultivating these disciplines in themselves and role modeling them for others. If leaders are not willing to do this, efforts to establish high performance at lower levels in the organization will be stymied, leading to frustration, resentment, and cynicism when people discover that their leaders do not hold themselves to the same standards they hold for those they lead.

When the disciplines of the Self and Interpersonal Fields are the norm for managing relationships, and the disciplines of the Team and Enterprise Fields are used routinely and are replicated throughout an organization, they establish a self-perpetuating system of highly effective leaders, teams, and individual contributors that collectively drive ongoing high performance. This self-perpetuating system is a leadership culture. Leadership cultures are enormously resilient to change—be it the loss of a leader, a major reorganization, mergers and acquisitions, or shifts in the marketplace. They are cultures of accountability, in which every person holds themselves accountable for their performance and is clear about their expectations of their leaders, peers, and followers. Commitments are managed effectively, and when a commitment is broken the skills to quickly and effectively deal with the situation are in place. And they are cultures of empowerment, in which every individual is expected, and has the capability, to innovate, lead, and execute effective action.

CONCLUSION

The disciplines of the Four Fields of Leadership require commitment and effort. The framework of the Four Fields makes it clear that the role of a leader is much more than making declarations and expecting people to fulfill them. Leaders must ensure that the disciplines of the Four Fields are in place throughout their organization, and must demonstrate these disciplines in their own behavior every day.

This paper presents a perspective on leadership and organizational culture that provides concrete principles and practices for establishing leadership cultures of high performance. Because of their well-defined nature, these principles and practices can be learned. A leadership culture can be intentionally developed by any organization willing to invest the time and effort. The rewards are great.