Creating an Agile Enterprise

Tom Goodell

Craig Thielen

Tom Goodell, Founder and President of Linden Leadership

Craig Thielen, Head of Digital Solutions at Trissential

© 2023 Linden Leadership, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

“We are all connected. Like our bodies, if one single molecule is off, then our entire bodies are affected. Organizing from this perspective allows us to see that it’s not enough for anyone of us to be okay if others are in dis-ease.”

– Rusia Mohiuddin, Emergent Strategy, 2017, p. 98

We met in the mid-2000s when Craig attended a leadership development program that Tom was helping to lead. Craig was deeply interested in the intersection of organizational culture, leadership, and business process. At Linden Leadership Tom was continuing to evolve the Four Fields methodology for creating leadership cultures that could be sustained for generations.1 We stayed in touch over the years, and as Craig became a recognized global expert on business agility, we came to the conclusion that the marriage of the Four Fields methodology with the principles of business agility would create the ultimate business outcome, a sustainably market leading enterprise. Out of that came a rich relationship that led to the writing of this paper.

This paper is based on our separate experiences and shared thinking with a variety of organizations on the challenges and opportunities of business agility and the culture and leadership required to enable it. Our work with Agile and adaptive enterprises is cutting edge thought leadership; it is not a methodology. Rather it is a set of principles and practices that we continue to evolve as we explore the transformation of organizations into agile enterprises. Our intent is to share our thinking and invite conversation.

The terms “agile” and “agility” are commonly used in business literature, but unfortunately in ways that are often inconsistent and unclear as to their precise meaning. This leads to confusion about what Agile is, what it means to be agile, and how agility can be cultivated. To avoid that confusion and to ensure clarity, in this paper we will use the following definitions:

- AGILE, as a proper noun, refers to a set of 4 values, 12 principles, and the “Agile Manifesto” established in 2001 for “better ways of developing software.”2 Numerous methodologies that attempt to cultivate these values and principles have been developed since then.

- AGILE, as an adjective, refers to something (e.g. a person, team, organization, animal, ecosystem, etc.) that exhibits agility.

- AGILITY is a noun meaning the ability to move, think, and respond quickly in changing circumstances.

Throughout this paper we will use Agile with a capital “A” to refer to the values and principles defined in 2001, and to the various methodologies that have been developed as attempts to formalize and cultivate those values and principles. We will use agile with a lower case “a” to refer to a person, team, or organization that exhibits agility. Thus an “Agile team” would be a team following an Agile methodology; an “agile team” would be a team that exhibits agility.

We will use the term agility to refer to the ability to move, think, and respond quickly in changing circumstances. Thus “enterprise agility” or “business agility” would be the ability for an entire enterprise or business to move, think, and respond quickly in changing circumstances.

These are important distinctions. It is possible to engage in Agile methodologies without achieving agility; it is possible to achieve agility without engaging in an Agile methodology. Nonetheless, the values and principles established in the Agile Manifesto can, under the right circumstances, be useful in creating agile enterprises. Much of the inspiration for this paper comes from our experiences observing and working with organizations that invested heavily in Agile methodologies and yet failed to achieve agility; and with organizations that strove to become agile yet floundered because they lacked a clear framework for doing so.

Human organizations have become more complex, volatile, and uncertain than at any time in history. This trajectory will continue for the foreseeable future, perhaps forever. Agile was originally conceived as a way to address the complexity, volatility, and uncertainty of large software development projects. Over the last decade, largely due to its success in the technology field, it has evolved into all areas of human enterprises and in virtually all industries, private and public sector alike. Agile introduced a powerful set of refinements adapted to the fast-paced changing world of technology and software. It was not, however, designed to scale beyond a team level and certainly not to an enterprise level. Nor was it designed to address the human dynamics necessary to put those methods into practice. The Four Fields methodology is specifically focused on the human dynamics necessary for organizations to succeed in today’s volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous world. This paper provides insights and practices for using the Four Fields methodology to develop agile enterprises.

Agile developed from the deep insights of a small group of software engineers in the mid to late 1990’s. Each had come to the conclusion that traditional approaches to software engineering were insufficient for the complex challenges presented by large scale yet highly decentralized and rapidly evolving application development platforms and technologies. Agile provided a brilliant set of values and principles, many of which evolved from the time-tested Lean body of knowledge. Lean emerged from the manufacturing industry in the mid twentieth century to deliver better quality and customer value in much shorter time frames than previously thought possible. According to the Lean Enterprise Institute, “Lean is a way of thinking about creating needed value with fewer resources and less waste. And Lean is a practice consisting of continuous experimentation to achieve perfect value with zero waste. Lean thinking and practice occur together. Lean thinking always starts with the customer.” When applied to software development, Lean sometimes reduced the software development cycle from quarters or years to weeks or months. The insights gained from Lean led to the values and principles that were famously memorialized in the Agile Manifesto in 2001.3 The Agile Manifesto, which was written to address challenges at the team level of software development, states that developers should value:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- Responding to change over following a plan

Decentralized software development on a large scale is one of the most challenging endeavors that human beings undertake. It requires the close coordination of many, many individuals, teams, and teams of teams, each with their own needs, desires, and ambitions. All of these individuals and teams must collaborate closely in designing and developing software to meet requirements. The more complex and leading edge the software, the more iterative and collaborative must be the development process among all stakeholders. Today, in our hyperconnected world, we are seeing the same degree of complexity and need for collaboration in all areas of organizations. An agile enterprise will use Agile values and principles to guide the behavior of the entire organization, not just software development or technology centered efforts.

Traditional approaches to software engineering attempted to fully define requirements before beginning software design and development. However, end users often can only tell software engineers what will work in response to what the engineers have already built. Experiencing and responding to the software enables users to better understand and articulate their needs. There is a conundrum here: in order to build software, engineers must know what end users need. But end users can only tell engineers what they need in response to using software that the engineers have already built. Agile resolves this conundrum by having short cycles of rapid iteration called ‘Sprints’ in the design, building, and testing of small software components, in close collaboration between engineers and end users. This necessitates constant experimentation, reflection, learning, and adjustments to evolve solutions in partnerships of trust and cooperation. None of this is possible in a traditional, hierarchical, linear approach.

AGILE MEETS THE FOUR FIELDS

One of the significant insights emerging from Agile is that human dynamics—the inner lives of individuals, the relationships they form with each other, the behavior of teams, and the relationships among teams of teams—are vitally important determinants of success at all levels of organizations. If human dynamics are not well managed, agility cannot be achieved.

Agile’s insights and behavioral recommendations are powerful. But the challenge of getting individuals, interpersonal relationships, teams, and teams of teams, to actually engage in the desired behaviors requires principles, disciplines, and practices beyond those identified by the founders of Agile. For example, Agile acknowledges the importance of characteristics like transparency, trust, and servant leadership, but does not address the deep challenges of fully understanding them and transforming behavior to accord with them. This is not surprising given Agile’s roots in software engineering, a highly analytical field of practice. Because of these limitations, Agile’s success in software engineering as well as enterprise transformation is often hit or miss. Achieving sustainable agility over extended periods of time is a major challenge, especially when people attempt to apply Agile values and principles outside of software development teams to achieve business agility. This is where the marriage of Agile and the Four Fields comes in.

THE FOUR FIELDS METHODOLOGY: BEING AGILE

Linden Leadership’s Four Fields methodology grew out of the challenge of getting increasingly diverse teams in increasingly large and complex organizations to successfully complete large, complex, and interconnected projects. At its core are practices to develop and maintain highly effective and adaptive leadership and teams, and to develop and maintain a highly effective and adaptive culture throughout an enterprise. The Four Fields methodology provides the necessary principles, disciplines, and practices to fulfill this purpose. Agile provides values and principles to guide teams in maintaining alignment and efficiently executing complex interdependent tasks. The Four Fields principles, disciplines, and practices enable individuals throughout an organization to live and behave in accord with Agile values and principles. Agile comes from the very specific domain of software development with a very specific focus on the local interactions of team members. The Four Fields comes from a very broad view, encompassing behavior from the individual, to interpersonal relationships, to teams, and to the entire enterprise. They are a perfect fit for achieving highly adaptive, evolving, thriving agile enterprises. The marriage of Agile values with the principles and practices of the Four Fields can fulfill the promise of both at all scales within an enterprise.

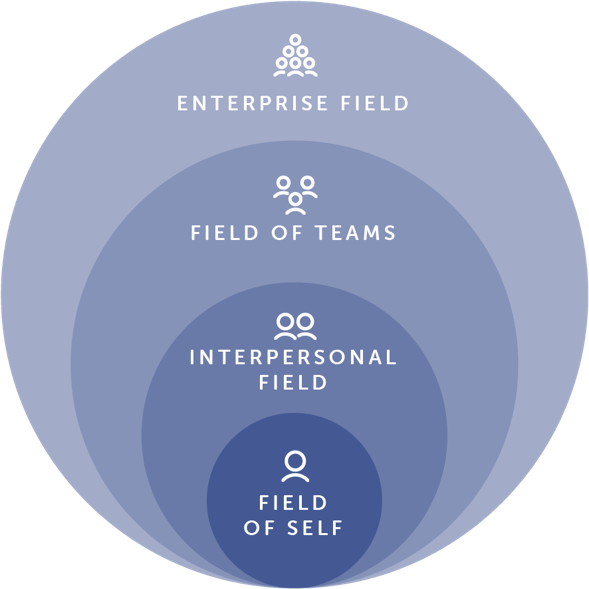

The Four Fields include the Field of Self, the Interpersonal Field, the Field of Teams, and the Enterprise Field as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The Four Fields

Agility in each field moving out from the Field of Self is dependent on agility in each of the inner fields. Agile focuses on the Field of Teams, but if the other fields are not sufficiently addressed, its effectiveness is severely compromised. This is the reason many attempts at implementing Agile fail. Without sufficient attention paid to the fields of the Self, the Interpersonal, and the Enterprise, the Field of Teams is fragile, difficult to establish, and always at risk of disruption. The Four Fields methodology comprehensively addresses the human dynamics of all Four Fields.

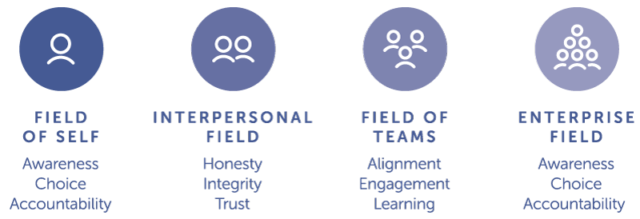

Each of the Four Fields has its own set of disciplines and practices for achieving agility, as shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Disciplines in the Four Fields

In the Field of Self a key discipline is awareness. Awareness is the ability to notice, and accurately interpret, what is happening in your self and in others. For example, being aware that the team you lead is not aligned around a shared goal is essential if you are to get the team on track and keep them there. Likewise, being aware that your trust in another person has diminished is vital if you must interact with them to get your work done. Kathleen, a leader we worked with in a distribution center, described her experience learning awareness practices: “Through awareness practices I realized that I often came into team meetings assuming that things would have gone bad. That was my mindset. When I started paying attention to how I felt prior to the meetings, and how that influenced my thinking, I realized there were things I could do differently. My behavior up to that point had caused mistrust to grow on the team. Changing my attitude changed the meetings.”

FIVE CHARACTERISTICS OF SUCCESSFUL AGILE TRANSFORMATION

Consulting with organizations of all types and sizes, in a wide range of countries and cultures, we have identified five critical characteristics of successfully achieving game changing outcomes of a truly agile enterprise:

- Becoming an agile organization is fully supported by senior leadership. It is acknowledged as a never-ending journey, not a destination. Leaders cannot delegate transformational change. They must apply it first to themselves, be a part of it, and lead it. As the great saying goes ‘Change thyself, change the world’.

- Transforming an organization is most effective when it is both ‘bottoms up’ and ‘top down.’ Bottoms up begins at the team level, often a few teams that demonstrate success, then naturally spawns into more teams. In each iteration of team expansion, they learn and adapt. Top down begins at the leadership level. The effort will fail if leadership is not participating and going through their own transformation to being agile.

- Being agile is emphasized over implementing Agile. While this may seem like a subtle distinction, it often makes the difference between success and failure. Leaders at all levels must recognize and accept that agility is a way of being and a mindset. Practicing an agile mindset leads to true behavior change, producing sustainable performance improvements that cannot be achieved by simply training on Agile methods and practices. Or simply put, ‘agile mindset over Agile methods’.

- Using transparency to build deep trust, recognizing when it is broken, and restoring it quickly, are constantly emphasized and reinforced.

- Shifting power and decision-making authority from a select few at the top of the organization chart to the team level and as close to the customer as possible. Leadership shifts from a hierarchal leadership model to a field leadership model.

You know you are on the right track when the journey shifts from being focused on Agile to being relentlessly focused on the customer, continuous improvement, continuous learning, and agility.

Increasing complexity, hyper-connectivity, and the need for diverse work groups to collaborate across geographical and cultural boundaries are becoming the norm for organizations. Becoming agile thus requires broad participation from stakeholders throughout an organization. And it is a long-term effort. Let’s take a look at how one manufacturing company we worked with implemented the five characteristics for becoming agile, utilizing the disciplines and practices of the Four Fields.

AGILE AND THE FOUR FIELDS IN PRACTICE

Maria, the CIO at Merva Manufacturing,4 was distraught. Two years into an Agile transformation effort involving more than 60 teams in the IT department there was, if she was honest, nothing to show for the investment. The teams had been trained on the latest Agile frameworks and methods but seemed to be going through the motions on practices. No measurable improvements to customer value were being realized. The company’s leadership was frustrated, as were the team members attempting to understand and implement Agile. Morale was low; and few participants understood why they were attempting this transformation, much less how to achieve it. The only thing holding them back from giving up was that they had not a clue what they would do instead. Maria reached out to us for help.

After observing her team for only one day, we had one question for Maria: did she want her organization to be agile, or did she want to implement an Agile framework? She looked at us quizzically.

An Agile framework is just a terminology for talking about specific practices for teams, and a set of guidelines for organizing work and collaborating. At that level, it’s really not much different from other project management methodologies. But becoming agile requires deep transformation of human dynamics—how people perceive and manage themselves, their relationships with one another, their teams, their relationships with the enterprise and with customers. You can implement an Agile framework, and nothing really changes, or you can transform the human dynamics of your organization to be agile and everything changes. This is where integration of the Four Fields methodology enters.

This was Maria’s aha moment. She realized her team had been implementing an Agile framework but had paid no real heed to human dynamics or mindset shift. They were approaching Agile implementation with the same mindset they had held throughout their careers—beliefs about what leadership is, what a team is, what an enterprise is, and what it takes to make all of those function well. They thought of Agile as a reorganization and technical skill set, not a transformation of how people think, relate, and make decisions. They had approached the transition to Agile with traditional training programs. But training is skill-based while transformation is based on personal insight and discovery. Training is largely a cognitive and muscle memory process. Transformation involves challenging your beliefs, deepening your insight into yourself, becoming more curious and open to others, and developing strong emotional intelligence.

CHARACTERISTICS 1 & 2: SENIOR LEADERSHIP SUPPORT & START SMALL

Maria now understood that she had mis-stepped on the first two critical characteristics of a successful Agile transformation: transformation should start with senior leaders, and initial teams should fully understand and be aligned with leaders’ vision, strategy, and objectives for the shift to being agile. They must understand the ‘why’ of the transformation and there must be alignment and feedback loops between upper management and the teams. Maria had not recruited sufficient support and buy-in from senior leaders and other stakeholders; and she had bitten off too large an effort to get started.

As she came to understand what being agile really means and what it entails, Maria engaged her colleagues in the C-Suite. She helped the CEO understand the pervasive transformation that would be required throughout the company, and the broad and deep value that could be created through increased efficiency, collaboration, and innovation in all areas of the business. She worked with the Chief People Officer to identify the deep ways in which becoming agile would support the leadership and culture initiatives that HR was leading. She worked with the leaders of marketing and manufacturing—two key areas served by IT—to help them understand that the transformation would take time but would, in the long term, enable far more rapid and effective responses to new opportunities and challenges. And she worked with the CFO to articulate the long-term financial value to the company. With the buy-in and engagement of the C-Suite she was ready to begin again.

As she gained support from senior leaders, Maria began conversations with stakeholders across the company to identify an appropriate area of the business to demonstrate the value of being agile. She wanted an example that would be small enough to manage with a handful of teams yet significant enough to demonstrate meaningful business value from becoming agile. Based on these conversations she selected a project for the Marketing Department. The project involved replacing a number of disparate home-grown and off-the-shelf software packages that Marketing had been using for years with one integrated software system that Maria’s team would build. She let people know that this was a pilot project taking a new approach to leveraging the principles and practices of Agile and the Four Fields. She asked for volunteers, knowing they would be more engaged and likely to succeed than people who joined because they were told to.

CHARACTERISTIC 3: EMPHASIS ON BEING AGILE, NOT IMPLEMENTING AGILE

Recall that the Agile Manifesto values individuals and interactions over processes and tools. Individuals and interactions are the product of human dynamics, which is why the disciplines of the Four Fields are so critical to becoming agile. This brings us to the third essential characteristic of successful efforts to become agile: being agile is always emphasized over implementing an Agile framework or methodology. Maria realized that another blind spot in her earlier efforts to bring agility to Merva had been thinking about it as a traditional project conducted with traditional training. She had not understood that agility is more about human dynamics than it is about project plans and schedules.

Being agile is much more than a process or even a method, it is a mindset based on a core set of values and principles. It is not just a set of rules to follow or steps to execute, it is a way of being and living that requires constant practice, reflection, adjustment, and learning. Just as a performing artist must continually practice their craft, so must one who strives to be agile continually practice this way of being. For teams to become agile, individuals on the team must adopt agility as an inner state, a way of being. Only then will the desired behaviors emerge. This may sound overwhelming, but the Four Fields methodology provides the disciplines and practices to achieve that inner state and to cultivate the interpersonal relationships, team dynamics, and enterprise culture necessary for an enterprise to achieve agility and to thrive.

Once she had her team assembled, Maria initiated the effort with a series of collaborative workshops we led that introduced the principal concepts of agility and the disciplines of the Four Fields. It was made clear from the start that this project would be quite different from what people were used to. Decision-making authority would be far more distributed and far less top-down. Building and sustaining strong, vibrant interpersonal relationships would be a constant theme and measure of success.

The workshops focused on the human dynamics necessary to adopt an agile mindset and to actually be agile in the way you manage yourself and your relationships with others. Our workshops thus emphasized developing deep self-awareness and using that self-awareness to develop greater emotional intelligence, techniques for self-regulation of one’s feelings and behavior, building vibrant relationships through cultivating high trust, and building strong, aligned, and adaptive teams.

The workshops challenged participants to understand how their beliefs, words, and actions influenced their relationships and the dynamics of their teams. Not everyone is open to such challenges. While most of the participants embraced this learning, a few did not. They were supported in their choices to leave their teams and move to roles that did not demand as much personal transformation.

Senior leaders, including the CEO and other members of the C-Suite, were included in these workshops. This made them and other participants uncomfortable at first, However, they also understood that old perceptions and traditional ways of relating across the org chart created barriers to the effective communication, systemic learning, and rapid adaptation that were required in order to become agile. Redistributing power and decision-making authority could not have happened without the participation of leaders in the transformation workshops.

In keeping with her understanding that the transformation to being agile is a long-term proposition, Maria planned the workshops to span the 12-month life of the effort. From that point forward the organization recognized the essential role of developing skill in the disciplines of the Four Fields when transforming into an agile organization.

CHARACTERISTIC 4: DEEP TRUST

The transformation in human dynamics that is required to become agile can only happen in the context of high trust among all members of a team, and in the relationships between teams. The discipline of trust in the Interpersonal Field is thus an essential foundation for success. Maria recognized this and, along with the senior leaders of the organization, understood that the necessary depth of trust was significantly greater than had been the norm in the organization. Indeed, it is significantly more than is the norm in most organizations today. This is the fourth critical characteristic of successful efforts to become agile: creating a culture of high trust.

To address this, Maria scheduled quarterly two-day workshops that included all team members and stakeholders in the effort. These workshops progressively broadened and deepened everyone’s understanding and skill in the disciplines of the Four Fields. They were also powerful opportunities for deep relationship building within and across teams. In addition to these quarterly workshops, regular team meetings emphasized the Field of Teams discipline of collective learning and the Interpersonal Field discipline of trust. Four Fields and / or agility coaches periodically attended team meetings to assess the health of the teams and the interpersonal relationships among team members. Team members were free to call on coaches at any time to help them with an issue or to support them in working out interpersonal challenges with other team members.

The result of this was that teams became self-healing, quickly addressing anything that diminished team performance as it arose. Over time, this built extraordinary trust within teams and across teams. When the project was completed, team members were able to bring their transformational learning to the next teams they joined, helping to disseminate the principles and practices of agility and the disciplines of the Four Fields throughout the organization.

If one person on a team is having a bad day, is unable to cope on some level, then to some degree the team is unable to cope. This is not a call for the person having a bad day to tough it out. Rather, it is a call for all team members to have each other’s backs, help each other out, and collectively address challenges and “bad days.” That’s the spirit of an agile team—everyone watches out for the health of the team. If two people are struggling with each other, which means their Interpersonal Field is in some degree of disarray, the team requires them to work it out because that is necessary for the well-being of the Field of the Team.

Team meetings thus included a review not only of how they had done on their goals since the last meeting, but also an assessment of the health of the team. How was each team member feeling, and what was the quality of relationships among them? It took time, but eventually the teams got to where they could have these conversations openly and honestly. If one team member observed others that appeared to be in conflict, they would name that, and the concern would be explored and addressed. If two team members needed support from a coach, then a coach would be engaged by them.

CHARACTERISTIC 5: SHIFTING POWER AND DECISION-MAKING AUTHORITY

When Agile was first conceived, the goal was to find better ways to develop software through high performing, tight knit, fully aligned, transparent and committed small teams. These teams typically have five to nine members. Guidance is provided about the values and principles to which the team should aspire, but it is up to the team to figure out the details of the roles, methods, and approaches that will work best for them to succeed on their project. No two teams do this identically because the personalities, skills, and experiences of team members and of the team as a whole are unique. For many, this ownership of how work will get done represents a significant change from the past, in which teams were not only told what to do but also how to do it. In many cases, unwillingness or inability to fully embrace the transfer of decision-making authority to individuals on small teams is the reason attempts to establish agile teams and organizations fail. It had certainly been a problem for Maria in her first attempt at bringing Agile to Merva.

This is the fifth of our characteristics of successful agile transformations: power and decision-making authority are shifted from a select few at the top of the organization chart down to the team level and as close to the customer as possible. Leadership shifts from hierarchical leadership to field leadership.

The workshops we conducted for Maria provided a context to collectively surface and discuss the challenges people were experiencing in becoming agile. Team members had sometimes been told they would be given decision-making authority but found that if their decisions were not liked by managers or leaders, they were overridden. This left team members discouraged and cynical about the commitment to agility.

The availability of coaches was another critical factor in Merva’s success. Especially in the first months of the effort, we were called on to intervene and help managers and leaders make the transition to accepting the decision-making authority of the teams. This was why it was so essential that leaders, managers, and all key stakeholders were involved in the workshops. In some cases, they had the most work to do in making the transition to being agile. And occasionally those challenges went all the way to the top of the C-Suite. Agility can be quite challenging for leaders used to command-and-control hierarchies.

Agility and field leadership establish great specificity, clarity, and alignment of purpose, with constant adaptive adjustments as circumstances change. Practices of specificity, clarity, and alignment are applied iteratively to guide execution at all scales of projects and, increasingly, all scales of organizational performance. Agility and field leadership establish highly effective teams for whatever specific conditions define a project. Achieving that level of specificity, clarity, alignment, and adaptivity requires mastery of the disciplines of the Four Fields.

Three months into the engagement, Maria knew it would be successful. She initiated the same program with three more teams, and the following year brought it to twenty more teams. Three years after beginning this journey, practices of agility and the disciplines of the Four Fields had become standard practices for how people worked throughout Merva, regardless of whether they were in technology or other areas of the business. Because stakeholders throughout the company were involved in these projects, business leaders and managers were also introducing practices of agility and the disciplines of the Four Fields to their teams. The transformation to enterprise agility was underway and demonstrating measurable customer value.

THE AGILE ENTERPRISE

BECOMING AGILE

Agile and the Four Fields methodology developed separately, in parallel, as different but complementary approaches to addressing the challenges of getting groups of people to collaborate efficiently and effectively at all scales of organizations of all sizes. Linden Leadership’s Four Fields and the application of Agile’s values and principles to enterprise-scale challenges were both responding to the increasingly complex business problems that arose in the rapidly changing hyperconnected world created by the Internet and telecommunications technologies. Agile was initially narrowly focused on software development, while the Four Fields was focused on the human dynamics that determine all aspects of organizational performance.

Becoming an agile enterprise requires transformation in all of the Four Fields—the self, the interpersonal, the team, and the enterprise. Agile team members must understand what it means to establish and sustain this agile mindset. They must be drawn to it with awareness of what it will take, and choose to accept the challenge. It’s not for everybody. Becoming agile means transforming yourself, continually, as a way of living and being.

Visionary leaders today are applying practices of agility and the disciplines of the Four Fields to broader and broader problems and exploring what it would mean for an entire organization to be an agile enterprise. This is inspiring a rethinking of the meaning of work, what it means to get work done, and how best to organize people. New ways of working to optimize operational effectiveness and maintain a focus on customer value are appearing. In the marriage of Agile’s principles and values with the disciplines of the Four Fields we are discovering increasingly powerful, deep, rich, and creative ways for individuals and teams to cooperate and thrive. As we continue to learn and leverage the best of both, the results will outstrip anything that could come from a traditional hierarchical, process-oriented mindset.

Everything is connected. You can’t change one part of an organization without affecting all parts of an organization. The spirit of both Agile and the Four Fields acknowledges this. They recognize that human organizations are living systems. Living systems are complex, and thus the future is always uncertain. This is a good thing; it means that the future has great potential for creative surprises and possibilities we could not foresee. But to embrace that, we must be willing to give up the comfort of rigid hierarchy, certainty, and control. Transformation is never done; it’s a way of being. Transformation becomes a way of doing business for practitioners of agility and the Four Fields.

TOM GOODELL

is President and founder of Linden Leadership. Linden Leadership’s mission is to guide clients in establishing and sustaining leadership and cultures of high performance. Tom is the author of the book The Four Fields of Leadership: How People and Organizations Can Thrive in a Hyperconnected World. The Four Fields methodology integrates powerful coaching methodologies, systems theory, emotional intelligence, practices of high-performance communication, and experiential learning. Tom provides executive, management, and team coaching; leadership training; and culture-building services in a wide variety of organizations, including entrepreneurial businesses, large corporations, government, education, and not-for-profit institutions.

CRAIG THIELEN

is a Principal and head of Digital Solutions at Trissential, an award winning management consulting firm focused on business improvement. Trissential is part of Expleo, a global technology & engineering leader with offices in 30+ countries. Craig is a globally recognized thought leader, speaker and writer on the topics of strategy, innovation, enterprise agility, data centricity, digital transformation, and culture. He is passionate about helping organizations realize their potential through building culture and capabilities for sustained competitive advantage.

© 2023 Linden Leadership, Inc.

- The Four Fields is a comprehensive methodology for establishing long-term sustainable cultures of leadership and high performance. It has been used in organizations of all types and sizes in numerous countries and cultures. Its application to leadership, culture, and organizational performance is explored in depth in Tom Goodell’s book The Four Fields of Leadership: How People and Organizations Can Thrive in a Hyperconnected World (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

- 2001. Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

- 2001. Manifesto for Agile Software Development.

- Merva Manufacturing and the people, events, and experiences described

here are a hybrid based on our experiences with several clients. We have

anonymized specifics sufficiently to protect confidentiality.